APOBEC enzymes, mutagenic fuel for cancer evolution

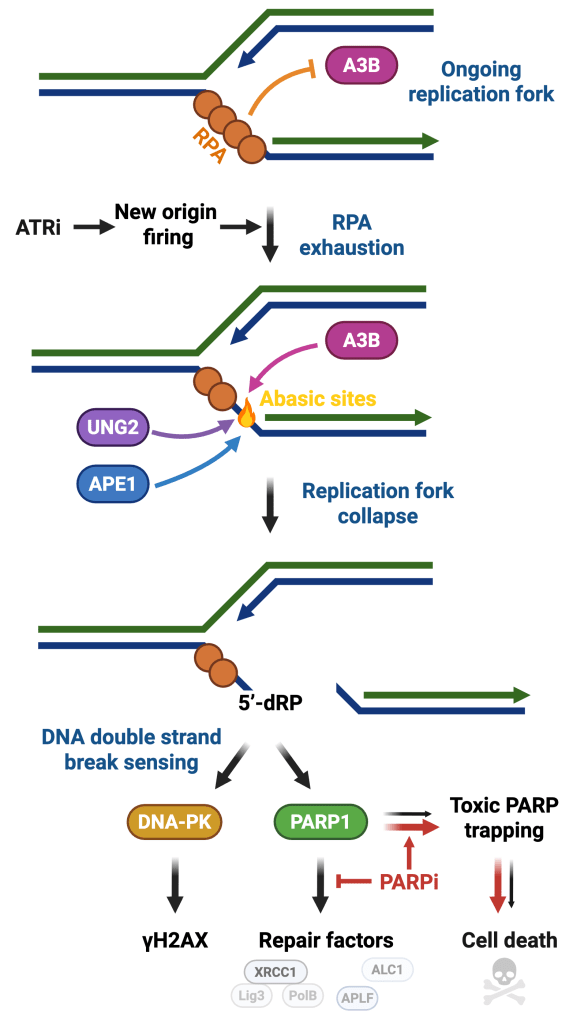

APOBEC3A (A3A) and APOBEC3B (A3B) are two members of the APOBEC family that promote the deamination of cytosine to uracil in ssDNA. A3A and A3B serve as essential components of the immune system, acting as defense mechanisms against viruses. However, APOBEC proteins are also one of the predominant causes of genomic mutations, DNA damage, and replication stress in cancer. Cancer-focused genomic studies have identified APOBEC-associated mutations in >70% of cancer types. Aside from inducing mutations in cancer genomes, A3A and A3B promote genomic instability by inducing replication stress, DNA double-strand breaks, and chromosomal instability (CIN). With this ability to rewrite genomic information and induce genome instability, A3A and A3B are considered to be major drivers of tumor evolution, thereby promoting disease progression and resistance to therapies. In the laboratory, we investigate the mechanism by which A3A and A3B induce mutations in cancer genomes (Buisson et al. Science, 2019; Jalili et al. Nature Communications, 2020; Isozaki et al. Nature, 2023, and Sanchez et al. Nature Communications, 2024) and develop new strategies to specifically target cancer cells that express A3A or A3B (Buisson et al. Cancer Research, 2017 and Ortega et al. Science Advances, 2025).

DNA damage response as a safeguard of genome integrity

Maintaining genome stability is a daunting task because each cell in the human body receives an average of 10,000 DNA lesions daily. Cellular DNA integrity is frequently compromised by endogenous and exogenous factors such as replication stress, APOBEC enzymes, UV radiation, or chemical agents that cause DNA damage and genomic instability. DNA damage response (DDR) plays a crucial role in maintaining genome stability by sensing DNA lesions and initiating signaling to promote temporary cell cycle arrest and DNA repair mechanisms. Although cells will repair most of the DNA lesions, excess damage will lead to the formation of mutations and chromosomal rearrangements that contribute to cancer. In the laboratory, we study DNA damage signaling pathways that detect and promote the repair of DNA in response to various genotoxic stresses (Bournique et al. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2025 and Ortega et al. Science Advances, 2025).

Innate immune responses to RNA viral infection

A critical issue in virus research is understanding how the host responds following infection to suppress viral replication and propagation. The innate immune response is the primary line of defense against viruses after they gain entry into cells. The first step of the innate immune response relies on the host cell’s ability to recognize conserved features of pathogens that are not present in the host. Once activated, the innate immune system triggers different types of responses to induce the expression of hundreds of genes necessary to eliminate the virus or to block host cell translation and limit viral protein production. However, there is still a critical need to identify factors regulating the host cells’ innate immune response to prevent viral replication. In the laboratory, we focused on studying factors critical in initiating the innate immune response to RNA virus infection (Oh et al. Nature Communications, 2021 and Manjunath et al. Nature Communications, 2023) and we developed a novel CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide screening method, called CRISPR-Translate, to identify regulators of the innate immune system in response to different types of RNA viral infections (Oh et al. PNAS, 2024 and Manjunath et al Nature Communications, 2025).